After 36 films, too much caffeine, not enough sleep, jovial conversation at the Imperial and a total divorce from 'real life' for 10 days, this entry of the Toronto Film Festival comes to a close. It was a great festival this year and as I sit here with my appetite for world cinema whetted, I count the days until next years festival. Here are my thoughts in general on this years TIFF, followed by a very short comment and numerical rating (out of 10) for each of the films I caught.

Danish cinema is on fire. I caught 6 Danish films at the festival this year: The Pusher Trilogy, Adams Apples, Manderlay and Dear Wendy. And they were uniformly excellent.

South Korea remains a country to watch for quality cinema: While I though The Duelist was too inconsistent to warrant a recommendation, Sympathy For Lady Vengeance was the triumphant closer to Park Chan Wook’s Vengeance Trilogy and April Snow was nearly perfect as well, I missed The Presidents Last Band and I regret that little bit of scheduling conflict.

Mainstream Hollywood Cinema can still be good: David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence walks the delicate line between genre and drama and is a mainstream film to boot. Another solid entry into the fascinating Cronenberg Canon. Also, Walk the Line was a solid tribute to Mr. Cash with compelling performances and great music. Finally, Thank-You for Smoking is a light and very fun satire on the Lobbying Industry.

Hong Kong action cinema can still Kick Ass: We will be raving about SPL until every fan of the K film industry, which has been ailing as of late, has seen it.

The Midnight Madness program has it’s strongest year since I’ve been attending: From stand up comedy to bovine horror played with nary a joke; from cult Thai madness to splatterfest horror-comedy; from a Miike family film that pushes the envolope of what a family film should be to an animated version of Romeo and Juliette which set to hip-hop; and finally from adrenaline pumping wish-fulfillment horror to the ultimate brand of HK coolness and French Parkour madness, this years line-up offered a host of fantastic fringe cinema. I’m speaking for everyone at Twitch when I say Thank-You Colin Geddes for a top-notch selection of the most twitch-friendly films at the festival.

Below are very brief thoughts (and a grade) of the 36 films which I managed to catch at this years TIFF:

Sarah Silverman: Jesus is Magic – Sarah is the best working female stand-up working today. Period. Other than the opening musical number, however, drop the sketches. (7/10)

Tideland – The film is watchable, but should have been a 45 minute short, not a 2-hour film. Rambling and redundant at times. A disappointment from a director that can’t seem to get a break these days. (3/10)

The Piano Tuner of Earthquakes – The Quay Brothers have an endless imagination and the film looks great. It is way to long, and the (intentional) lack of narrative coherence becomes intolerable around the 80 minute mark. (5/10)

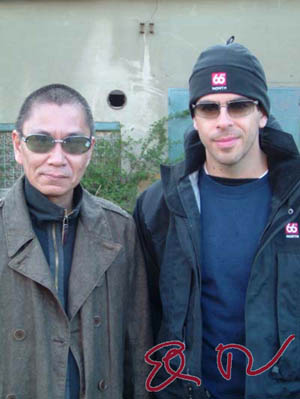

Takeshis' – You will get out of the film what information on Kitano you bring in with you. The ultimate insider film. (7/10)

Pusher – Gritty, visceral and willing to go to the bitter end with the story. Drug films are rarely this good. (9/10)

With Blood on My Hands - Pusher II – Bringing family into the equation elevates the sequel above the original. Stunning performance by Mads Mikkelsen. (10/10)

I'm the Angel of Death - Pusher III – Hard hitting, and often blackly comic, the third entry of the trilogy is the weakest, but only barely so. (8/10)

Saints-Martyrs-des-Damnés – Visually and thematically interesting, but a little bit overwrought at times and just didn't completly grab me, probably because I'm already familiar with Twin Peaks. (6/10)

Evil Aliens – Energetic, Funny, and gory entry into the Splatterfest genre. Wears its influences a little to closely on its sleeve though and ends up playing like a cover-album to innovators Raimi, Jackson and Coscarelli. (6/10)

A History of Violence – Successfully walks the delicate line between genre and drama. It is a mainstream film with something to say and another solid entry into the fascinating Cronenberg canon. (9/10)

Shark in the Head – Tiny, intimate film with something meaning to say about schizophrenia. Also melancholic for the loss of something that has just always been there. (7/10)

Isolation – Surprisingly solid straight-up suspenseful horror-pic. The scenes on the farm are creepier than when the film decides it wants to be Alien. (6/10)

Revolver – Guy Ritchie’s attempts at the deconstruction of the art of the con are not nearly as smart as he think it is, but the film is harmless fun. (6/10)

Caché – Creepy and unsettling take on racism, classism and terrorism. The violence in the film is about 5 seconds long, but it will haunt you for a while. (9/10)

The Proposition – Gritty Aussie western which paints the taking of the interior frontier as a string of incompetent blunders. Bloody and affecting and a cast that is willing to get down and dirty. (7/10)

A Little Trip to Heaven – Set in America, filmed in Iceland. A truly original look, sound and feel that is coupled with a fine Forrest Whitaker performance. (8/10)

Bangkok Loco – Thai Insanity that manages success despite overwhelming odds. One of the best opening credits sequences in a film. EVER. (7/10)

Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story – 24 Hour Party People meets Adaptation. Not a single moment of this film is unfunny. (9/10)

Souvenir of Canada – Let’s celebrate the mediocrity of Canadiana. Go Canadian Shield! (6/10)

The District! – Gorgeous Animation, well executed idea. Curiously light on humour. You have to read fast if you want to keep up with the subtitles of Hungarian Gangster Rap. (7/10)

Walk the Line – Top-shelf performances from Phoenix and Witherspoon. Great Musical numbers. Not as dark as I thought it would be. When given the choice to print the Truth or the Legend: They should have printed the Legend. (7/10)

Manderlay – Solid, but slightly more conventional than Dogville. Lack of a couple key actors from Dogville hurt the film a tad. (7/10)

Diameter of the Bomb – Not as impactful as I thought it would be. Too much focus on one victim of the suicide bombing to the detriment of all the other stories. (5/10)

The Duelist – Some gorgeous stuff in this incoherent genre-mash. Bad direction choices and inconsistent tone may be a result of my expectations, but I still didn’t like the film as much as I wanted to. (4/10)

The Grönholm Method – My biggest surprise of the festival which creates a new grifter-classic by blending the styles of Mamet, Lumet and LaBute. (9/10)

Time to Leave – Lightweight Ozon. Melodrama which offers a fresh take on 3-way sex, but doesn’t say much new on the subject of dealing with a terminal disease (6/10).

Sympathy for Lady Vengeance – A sublime closure to the Vengeance Trilogy, which appropriately deals with Atonement. Great visuals and direction anchored around a complex performance by Yeong-ae Lee. (10/10)

The Great Yokai War – High on creativity. Pushes right through the envelope of what exactly is a family-friendly adventure. Overlong by about 15 minutes and a weakly written lead character keep it from truly shining. (7/10)

April Snow – Pitch perfect tone and acting. The nature of the subject may cause some to find it a tad slow though. You’ll find yourself comparing this to In the Mood for Love, and it is just up to that standard. (8/10)

Seven Swords – Biggest disappointment of the Festival. Bad acting, bad lighting, bad direction, bad storytelling. Just Bad. (2/10)

SPL – HK cinema has a new shining star in the Firmament. Enough praise cannot be heaped on this new classic in the genre. (10/10)

Dear Wendy – Von Trier and Vinterberg give this rumination of what guns mean to Americans a lot of sizzle to go with the substance. The ending is telegraphed, but getting there is a blast. (8/10)

Adam's Apples – Pitch black comedy which is audacious and warmly charming. It breaks nearly every form of political correctness with a certain glee and gets away with it too. (8/10)

Hostel – Solid entry into the genre which pumps the adrenaline and isn’t shy about the violence or the sex which are mixed nicely in the subtext. (9/10)

The Willow Tree – It’s hard to like the selfish main character in the film, but you can feel his pain as he has to cope with the gift of restored sight after 38 years of blindness. It is watchable, but nothing special. (6/10)

Thank-You For Smoking – Lightweight and unabashedly mainstream satire. Not as good as wag the dog, although it really wants to be. The large ensemble of talented actors are game to the movies sprawling meanderings. (6/10)